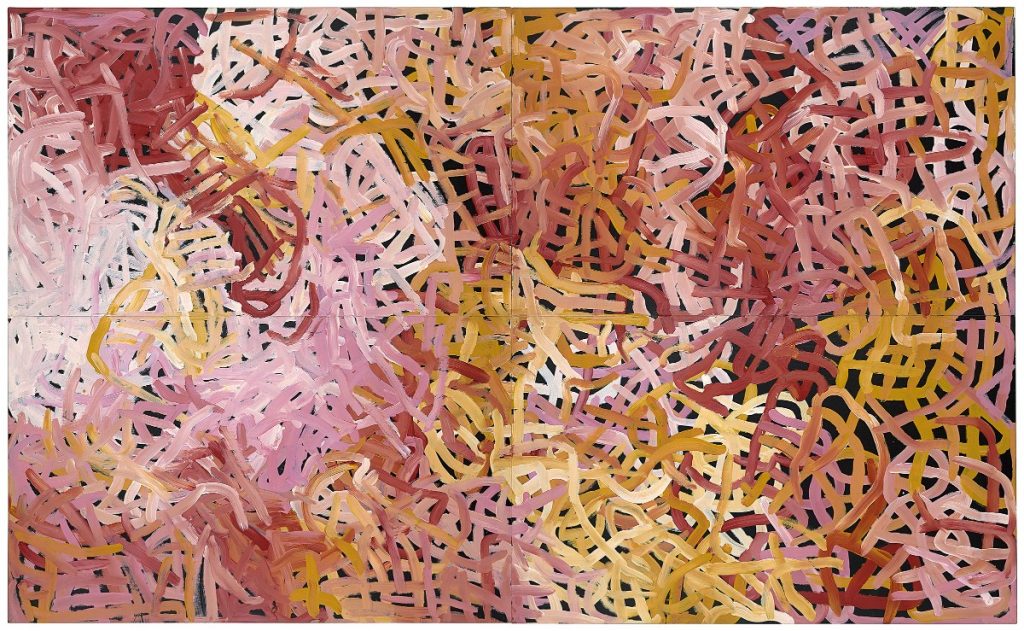

Emily Kam Kngwarray – Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam), 1996 – 245 cm x 401 cm – Synthetic polymer paint on canvas © The Artist – Image courtesy National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

A major exhibition titled Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia opens on February 5, 2016 in the galleries of one of the most prestigious American university, the Harvard Art Museums.

To ensure that it reflects the authentic perspectives and experiences of Indigenous people, the show has been guest curated by Stephen Gilchrist, who belongs to the Yamatji people of the Inggarda language group of Western Australia and is currently an associate lecturer at the University of Sydney.

The exhibition takes its title from the neologism “Everywhen”, coined by Australian anthropologist William Scanner to describe Indigenous conception of time as a cyclical and circular order where past, present and future are interconnected.

The exhibition aims at positioning Indigenous art not as “other”, but at another form of contemporary art. The 70 selected artworks, many of which had never left Australia before now, highlight the role of Indigenous artists as couriers as well as keepers of an ancestral culture and hence demonstrate that these artists don’t belong to the past, but are the actors of a vibrant and living artistic practice.

The works, in various media (sculptures, bark paintings, oil on canvas, and photographs) were created for most within the last 40 years, by some of the most significant contemporary Indigenous artists, including Rover Thomas, Emily Kam Kngwarray, Judy Watson, Vernon Ah Kee and Christian Thomson.

American audience is not that familiar with Australian Indigenous art (this exhibition is the largest of this kind for more than 25 years in the US), and curator Stephen Gilchrist seized this “opportunity” to present a personal view of Aboriginal culture, with an innovative exhibition design. For Gilchrist, the division between anthropology and art is artificial, “Art and practice are like hardware and software” he says, they need to be seen and understood together. Indeed, the artworks are showcased alongside historical and cultural objects, such as vessels and baskets, collected by the Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in the 1930’s.

Furthermore, the works are not classified as usually seen in exhibitions by period, medium or geographical origin, but by specific thematics : Seasonality, Transformation, Performance and Remembrance. In this way, the exhibition explores how time is embedded into indigenous artistic, social, ecological, historical and philosophical life.

In conjunction with the exhibition, the first large-scale technical examination of Indigenous Australian bark paintings was carried out by researchers at the museums’ Straus Center for Conversation and Technical Studies. This study makes his mark in history of art, as results proves that binders such as orchid juice and bloodwood were used far earlier and more widely than previously assumed. They also analysed the chemical composition of pigments used in painting, and surprisingly came upon a few nontraditional pigment sources, including blacks made from cell batterie, and silver pigment from the corrugated rooftops of buildings.

The research is still ongoing, with the objective of making a more comprehensive “atlas” of Australian pigments.

SOURCE: Harvard Art Museums

ARTICLES:

– McQuaid, Cate, ‘Illuminating indigenous Australian art at Harvard‘, The Boston Globe, 31 January 2016

– Smee, Sebastian, ‘Eye-opening Australian Aboriginal art at Harvard‘, The Boston Globe, 4 February 2016

– Cuthbertson, Debbie, ‘American Dreaming: Aboriginal exhibition at Harvard Art Museums challenges notions of time’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 2016

– Lawrence, Lee, ‘Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art From Australia’ Review‘, The Wall Street Journal, 15 February 2016

– Nguyen, Sophia, ‘At the Harvard Art Museums, Indigenous Australian Art and Thought on Display‘, Harvard Magazine, 17 February 2016