ABORIGINAL ART: ORIGINS

Aboriginal art is based on the stories and traditions of the creation of the world (often referred to as “dreaming” or “Dreamtime”) during which the creation ancestors embarked on great journeys across the Australian land, shaping and giving it its most characteristic features, creating its flora, fauna, people and celestial bodies. These stories have been passed down for thousands of year, reenacted through the performing of ritual ceremonies. They dictate Aboriginal customs and laws. At the very core of Indigenous people’s beliefs, lies the essential, inalterable relation established between the land and the people, which functions according to dynamics of interdependence, where one cannot exist without the other. There are many creation stories across the regions of Australia. Customs and laws are reaffirmed through traditional ceremonial practice, but they also open up to today’s realities and incorporate contemporary events. All these elements contribute to defining the Aboriginal culture as one of the oldest, still living traditions in the world, capable of lasting by adapting and anchoring itself in both ancestral traditions and present times.

Aboriginal art, in its traditional sense, expresses itself through dance and songs, sand and body paintings, rock petroglyphs and paintings and the craftsmanship of sacred objects. These are the manifestations of the dreamtime stories, as well as a way to visually pass on traditions to new generations.

The oldest forms of Aboriginal art which can still be seen today have been dated as far back as 60,000 years ago. It is believed that there are over 100,000 ancient Aboriginal art sites throughout Australia, and new sites are still being discovered at regular intervals.

ABORIGINAL ART: BIRTH OF A MODERN MOVEMENT

The earliest collections of Aboriginal art were assembled by ethnographers and anthropologists, from the beginning of the 19th century onwards. Some of the first artists included William Barak, an Aboriginal tribal leader from Coranderrk, near Melbourne, Tommy McCrae or Mickey of Ulladulla. However, these artefacts were viewed primarily as ethnological objects. In 1929, the National Gallery of Victoria showcased the first comprehensive exhibition of bark paintings and indigenous artefacts ever held in a public art gallery.

In the early 20th century, the Hermannsburg mission’s pastor, J.W. Albrecht, encouraged young Albert Namatjira to express his artistic talent. However, it wasn’t until the early 1930s, following a meeting with the artists R. Battarbee and J. Gardner, that Namatjira started to develop incredible skills in watercolour. He held his first exhibition in 1938, encountering immediate success, and pioneered a style still continuing today. Other community workers started persuading Aboriginal people to paint.

A movement was also launched at Ernabella in 1954, where people painted traditional motifs using bright acrylic paints, which became known as “walka” designs, but it only met with little success at the time.

Amidst all this activity, Aboriginal motifs and sacred images started being used commercially as designs for everyday products, such as tea towels, sparking a real debate on whether such cultural misappropriation could be permitted. In this context, a young teacher, G. Bardon, walked into the desert community of Papunya in 1971. Having witnessed children drawing in the sand, he encouraged them to depict their stories on paper in the classroom and eventually talked the community elders into painting a mural on the new school building. Enthused by this new way of communicating their stories, the whole community soon started painting on anything they could find, including discarded chipboards and crates. In August 1971, a Papunya artist, Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, won first prize at the Caltex Art Award in Alice Springs. In 1972, Papunya artists decided to establish their own cooperative to function in a more organised manner and manage the growing stock of works they had already produced (estimated at over 1,000 in 18 months).

By the mid-1980s, this painting movement had spread widely through central Australia and art centres were established at Yuendumu, Balgo Hills, Lajamanu and Haasts Bluff. Developments followed in the same fashion throughout Australia, including the Kimberley region, Arnhem Land and much of the other states and territories.

ABORIGINAL ART: RESOLUTELY CONTEMPORARY

Following the creation of community-owned art centres throughout the land, Aboriginal art has been gaining tremendous momentum and popularity both in Australia and internationally.

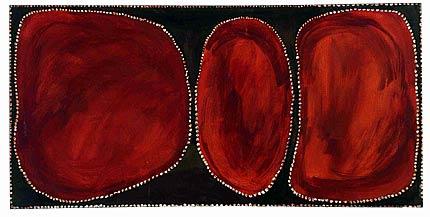

Rover Thomas – Uluru

The 1990s saw some major stylistic breakthroughs led by pioneering artists such as Rover Thomas and Emily Kngawarreye, whose popularity created an impulse towards heightened abstraction, resulting in the crafting of increasingly raw and gestural art. Thomas and Kngwarreye’s impact was also tremendous on the international arena as representatives of Australia at the 1990 and 1997 Venice Biennale of Contemporary Art. The positive reaction they received contributed to the generalized acknowledgement of Aboriginal artists as true contemporary masters, as well as to reigniting the interest for abstract, avant-garde painting in Australia.

During that period, most public museums in Australia opened galleries dedicated to indigenous art. A growing number of leading solo exhibitions also increased the profile of Aboriginal artists.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

One of the most surprising phenomena is that some of the newest painters and greatest revolutionaries of the art are indeed older artists, well into their 70s or 80s. Renowned late bloomers include Kimberley artist Paddy Bedford, and Yulparija elders Weaver Jack, Lydia Balbal and Jan Billycan. Numerous elders are also emerging from the astounding growth area of the Far Western Desert, at the junction between the three states of SA, WA and NT, where over 15 new painting communities were recently created. Their styles are characterized by an intense freshness and the use of vibrant colours, making the artworks truly capture and render the deepest of emotions.

Lydia Balbal

This last region was most recently put to the fore, with the unprecedented Felton bequest acquisitions and following seminal exhibition ‘Living Water: Contemporary art of the Far Western Desert’ at the National Gallery of Victoria.